Into the Breach

Explaining the Challenges of the Modern Combined Arms Operation

There’s a lot more to modern war than drone swarm highlight reels and artificial intelligence. Tempo, mass, logistics, fires, geography, weather, morale, and more all impact the lowest private to the highest general. And there is one spot on the battlefield where all of those factors weigh heaviest on the soldier. Here, you’re pitted against planned enemy defenses, heavy fire, poor visibility and comms, with casualty expectations that can best be described as “good luck.” I am of course talking about the combined arms breach, which can show you the whole story of modern war in just a few minutes.

In simplest terms, the combined arms breach can best be described as the most complex operation on the ground requiring the most planning, rehearsals, synchronization, resources, and bodies. You are attempting to punch a hole into the enemy’s defenses, likely somewhere the enemy has identified you will do so, so your forces can quickly rush through and get behind enemy defensive lines in the hopes of catching them out of position and exploiting this rapid shift of battlefield geometry to your advantage. If you fail, you are caught in the open, there’s a traffic jam of friendly forces behind you and every available enemy asset yeeting ordnance (including artillery-launched mines to trap you) in hopes of making you Go Away. I’ve previously talked about the evolution of combined arms warfare, but in this article I want to specifically focus on the breach because it is the hardest problem and one which spooked the US Army when Ukrainian counteroffensives began failing against well-planned Russian defenses in 2023.

Who does the breaching?

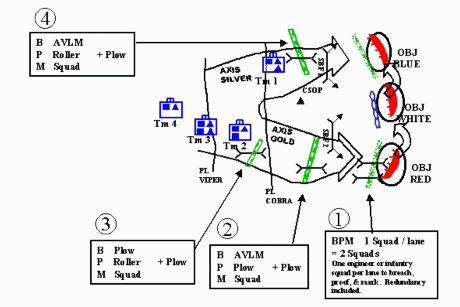

A combined arms breach is conducted by a mix of units operating in sync. Technically, a platoon or company can do it organically against light defenses, but against planned defenses you will likely need a lot more to get the job done. In reality, you’re looking at a Brigade, Division, or Corps level operation (thousands to tens of thousands of soldiers) working in concert to get the job done. Depending upon available avenues of approach (read: potential breach points that support the movement of friendly forces), you can have one or multiple breaching lanes open during an operation. These may all be conducted at once or tied to specific lanes being opened first depending on factors ranging from enemy response to friendly resourcing. In a large scale operation, the breachers are likely combat engineers trained in explosives, mine clearance, wire cutting, and other techniques. Depending on the enemy’s defenses and assets available, the engineers may clear these with anything ranging from wire cutters to bulldozers to Mine-Clearing Line Charges (MICLICs). These engineers are supported by infantry and armor who provide security and direct fire support leading up to and during the operation. Artillery provides cover with smoke shells and high explosives against priority targets, and air assets ranging from drones to helicopters and jets soften targets further behind the front lines to disrupt or delay the enemy response. If the operation is large enough, you’ll even see cyber and electronic warfare operations to strike certain infrastructure targets or disrupt enemy communications to delay their response.

What do you do in a breach?

SOSRA: Suppress the enemy, Obscure their line of sight, Secure the near side of the breach lane, Reduce the obstacles, Assault through the lane.

In a large scale operation you will encounter what we refer to as complex obstacles: different defenses interwoven with multiple obstacles (concertina wire, mines, trenches, etc). You will need to create a lane wide enough for friendly traffic all the way through to a (relatively) safe zone. So you need to synchronize how you work your way through these obstacles in the most efficient manner with the most assurances that those obstacles are in fact defeated. You will (obviously) need to shoot back at the enemy while doing this and you will need to clearly communicate with friendly forces for both safety and effective employment of costly resources (like precision munitions or smoke). You will need to do this quickly because your friends only have so much ammo and so much smoke (measured in tens of minutes) to clear a hole that could be hundreds of meters long. The enemy’s reinforcements are also on their way. So the engineers blow up some mines and cut some c-wire, mark their lanes (so you don’t drive into the rest of the mines) and secure the far side of the breach with the infantry. All this time, everyone is shooting specifically at *you* and they likely pre-planned artillery and other fires because there are only so many good spots to conduct a breach in a given line. Oh, did I mention defense-in-depth?

What’s the modern challenge?

Congratulations, you’ve made it through the breach and have made it to the far side and set up security. That was hell and half of your engineers are wounded or dead. The first tanks are rolling through and pushing forward. Only there’s one small problem….about half a kilometer down the road is another set of obstacles. And then another set 2 km behind that. And so on. In Eastern Ukraine, the Russians rapidly established defensive lines dozens of kilometers deep. Meaning the resources required to breach Russian defenses were enormous, thus either draining resources elsewhere from the Ukrainians or grinding their axis of advance to a complete halt as they slogged with fewer forces than necessary through Russian defenses. This much was present during World War I and shows how quickly maneuver can turn to attrition.

The modern breach is compounded by pervasive and cheap ISR techniques from roadside cameras connected to Wi-Fi for early warning to overhead satellite constellations. And while these systems can be spoofed, degraded, and deceived, it’s a constant battle to poke out the enemy’s eyes while protecting yours. So you have to add even more planning and additional enabling elements to your breach. More subtasks in your operation means more things that can go wrong or threaten the operation by giving away the target. Let’s not forget about the proliferation of precision fires from one-way attack drones armed with collection mechanisms and warheads so they can pass back intelligence to the second and third waves of strikes before they identify and strike their priority targets. This all makes breaching that much more costly and the breach site even more deadly, demanding more and more resources from the attacking force. This is why both Ukraine and NATO nations (including the US) are researching and testing autonomous systems specifically for the combined arms breach. If we can perfect the equation for cost x mass x efficiency for autonomous systems in the breach then we can successfully restore the attacking force advantage. And as an expeditionary force, the US Army favors the attack and maneuver, rather than planning for heavy, slow attrition in the offense (defense is a different story and for another article.)

Where is the Army falling short?

As with many other operational challenges, the Army has spent the last few decades emphasizing precision and exquisite over plentiful when it comes to munitions, equipment, and people. Exquisite systems have their place in modern war, despite what some may tell you, but they can only do so much in such a crowded battlespace. When I did my first combined arms breach at the brigade level at the National Training Center in California, we punched a lane through a single set of complex obstacles without consideration for having to think about doing the same thing a kilometer away or with a swarm of drones in the sky. Pretty much anyone who has went to NTC has done this or a version of it. And it still sucks. And you know what? Even if we tried to perfectly replicate Eastern Ukraine in a training environment, what would be the point?

Sure, training against drone swarms and booby traps is important, but after your third trench crossing that’s not an evaluation of a unit’s combat readiness (which is the purpose of places like NTC), that’s an evaluation of national policy and military force design. Where the Army failed was in thinking that the testing grounds of NTC were the end-all for combined arms evaluations. And to be fair, in 2022-2023 there were maybe a few dozen officers who’d been present for any combined arms breaches in the Thunder Run to Baghdad (which were nowhere near as hard) and maybe a handful that remembered Cold War era wargames when they were junior officers (which even then was still a maneuver game).

Where the Army did focus on new technologies and threats, they focused on the tactical level: how do we deal with mini drones collecting ISR? How do we intercept and outrange Russian artillery? how do we kill Russian armor columns? All of these are important questions but the Army missed the forest for trees. They missed how all of these threats and technologies would combine into one larger picture where a defensive Russian lines extend for hundreds of kilometers and sit dozens of kilometers deep. And for Ukraine, they’re limited by available systems donated or sold by NATO members and by simple manpower. At the end of the day, blood and steel still dominate the mathematics of the battlefield. The US Army is now waking up to this and starting to research and invest in potential solutions, but it’s only the beginning of a new arms race. Even if/when we do solve the equation for autonomous breaching so we can apply fewer costly resources to a greater area, we will still have to throw humans into the breach because surely new autonomous defenses will have defeated the autonomous breachers. Ukraine has demonstrated over and over that technological advantage is forever and rapidly fleeting. Or as MP Ferguson argues in TNSR, humans will become the new high-value target when drones cheaply proliferate requiring us to once again reconsider how we approach warfare.

Why does it matter for the Pacific?

If some day we must once against go to war in Europe, the Army has to have this problem solved. But this isn’t a Europe blog, So what does this all matter for the Pacific?

“Tony, there’s no wide open spaces in the First Island Chain like Eastern Ukraine for massive combined arms warfare by mechanized units.”

Well, defensive obstacles can come in many forms and for many reasons. And you know who has to breach a bunch of mines and terrain-integrated defenses in a short amount of time with armored vehicles while under fire from a world of hurt?

The People’s Liberation Army when it tries to invade Taiwan. You better believe they’re paying attention.

Eventually, we’ll probably have to take a few islands back ourselves. And you don’t want to be the man or woman in the breach figuring this all out for the first time.

If you would like to read more about the future of US-China conflict, the failures of US foreign policy, or what happens next, check out my novel, EX SUPRA. It’s all about the world after the fall of Taiwan, an isolationist and hyper-partisan America, and World War III. It was nominated for a Prometheus Award for best science fiction novel and there’s a sequel in the works! Don’t forget to share and subscribe!